Access to health care is a human right, but in West Africa, weak governance routinely erodes that right, as health systems remain chronically underfunded and poorly coordinated.

Development Diaries reports that decades after the Abuja Declaration, most governments still spend less than half of the 15 percent of budgets they pledged for health.

The average African country allocates only about 7.4 percent of its national budget to health, meaning critical services, such as clinics, trained nurses, and medicines, are always inadequate.

In Nigeria, only about four percent of government expenditure goes to health, with similar shortfalls in Senegal, Ghana and other West African states.

This funding gap drives inequality, as rural clinics run out of supplies, mothers give birth without skilled care, and many households face crippling out-of-pocket fees.

In practical terms, underfunded systems have high maternal and infant mortality and low life expectancy – a direct outcome of weak institutions failing to prioritise citizens’ needs.

Governance failures cut deeper, with corruption, bureaucraticinertia, and political instability sapping what little investment exists. A recent analysis of 15 West African countries concluded that poor regulatory quality and ineffective government ‘exacerbate poor health indicators’ like maternal and child mortality.

In other words, even the money governments do spend often does not translate into actual care. Policymaking tends to be top-down, with national elites making decisions that do not reach border regions or urban slums.

Crucial programmes like malaria prevention or routine immunisations suffer from weak implementation and lack of accountability. And cross-border health threats only highlight these faults.

Regional bodies like ECOWAS have frameworks for epidemic response, yet enforcement is minimal. As a result, national health policies often ignore migrants, youth, and women who cross borders or live in informal settlements.

When a disease outbreak occurs, it quickly spills into neighboring countries, showing how ‘national-only’ responses leave gaps.

Who is most hurt by this governance gap?

Again, it is the vulnerable women who need maternal health services; children and adolescents, who need vaccinations and youth-friendly clinics; refugees and migrants, who often lack legal access to care; and remote border communities.

These groups struggle even to get basic antibiotics or prenatal checkups. For example, a displaced family on the Niger-Burkina Faso border often ends up without any affordable clinic, simply because no one took responsibility for cross-border health provision.

In this case, responsibility rests squarely with governments and ineffective regional institutions. Each state has ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and often even domestic laws guaranteeing the right to health and life – yet they routinely under-invest and mismanage health systems.

Parliamentary leaders and health ministers must answer for failing to meet their constitutional duties. At the same time, ECOWAS and the West African Health Organisation (WAHO) have the authority to set regional health standards but lack enforcement teeth. Without a supranational court or binding treaty on health, member states feel little pressure to comply.

Citizens can push for change by demanding transparency. Ask your parliaments to publish detailed health budgets and spending reports. Civil society can use media campaigns or FoI laws to uncover how funds are, or are not, used.

You can push for regional compacts by advocating for ECOWAS to negotiate a health accord, with real penalties, rather than just declarations.

Form health committees to monitor local clinic performance and shortages, putting pressure on officials to act.

Ultimately, no global funding or fashionable summit can replace responsible leadership. So governments must turn budgets into clinics and policies into services. When they fail, ordinary people lose their lives and livelihoods.

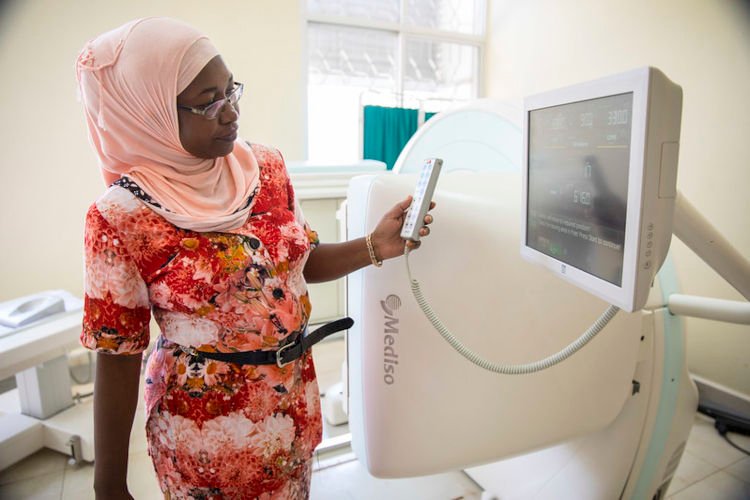

Photo source: IMF