The Nigerian government’s order for the free installation of 3.4 million electricity meters and its warning against consumer extortion sound promising, but there is more to Nigeria’s electricity setback.

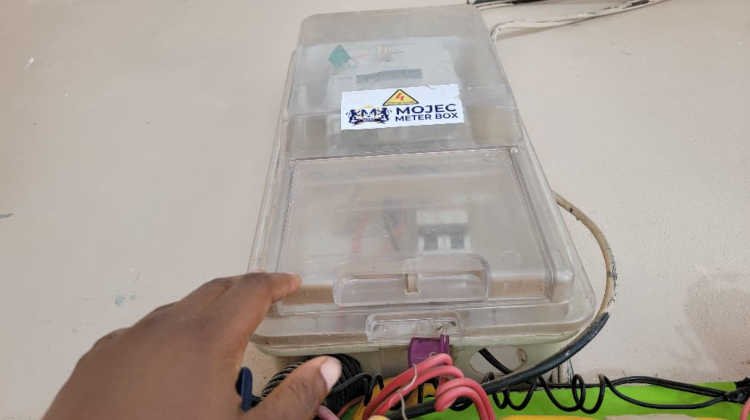

Development Diaries reports that the Minister of Power, Adebayo Adelabu, has announced the government’s effort to close Nigeria’s estimated seven million electricity meter gap with the deployment of 3.4 million smart meters, taking delivery of 500,000 units in the latest tranche.

The minister also warned that electricity distribution company (DisCo) officials and installers found extorting consumers will face prosecution, because the meters were procured under the World Bank–funded Distribution Sector Recovery Programme (DISREP) and must be installed free of charge.

Just days after the announcement, the national electricity grid collapsed, plunging the country into darkness, which is a reminder that the electricity crisis in the country is not limited to billing disputes alone.

The grid collapse, however, highlights an equally important truth that metering alone will not fix Nigeria’s electricity crisis.

For years, estimated billing has been declared illegal, yet millions of households still pay for electricity they did not use, paying for darkness and even air.

This shows that the real problem is weak enforcement, because when rules exist only on paper, silence from regulators and institutions is sabotage.

Metering improves billing fairness, not power availability. Structural issues remain untouched, with weak transmission networks, gas supply constraints, poor maintenance, tariff politics, and DisCo inefficiency common.

Although the government insists that these meters are free, consumers continue to pay bribes for installation.

A meter is not a favour from a DisCo official; it is a consumer right under Nigeria’s electricity regulations. Extortion thrives because complaint systems are unclear, sanctions are rare, and prosecutions are mostly talked about, not seen.

This issue has strong poverty and gender dimensions. Women-led households often spend more time arguing over bills, small traders lose income due to erratic charges, and poor families disconnect or turn to unsafe energy sources.

Citizens must stop treating electricity as a favour and begin defending it as a right. Nigerians should refuse to pay for meter installation, document any demand for money, and report extortion to the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) and consumer protection units with clear evidence.

Instead of negotiating alone, communities should organise collective complaints, demand written explanations for their bills, and actively challenge estimated charges.

At the same time, institutions must match words with action by publishing DisCo-by-DisCo metering rollout timelines, publicly naming and prosecuting offenders, enforcing automatic billing caps for unmetered customers, and mandating refunds for illegal charges.

Citizen monitoring must also be built into the DISREP process, because without public oversight, free meters will remain free only in government statements, not in people’s homes.

Photo source: Development Diaries